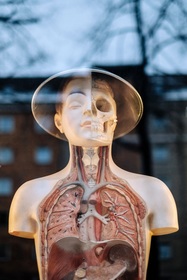

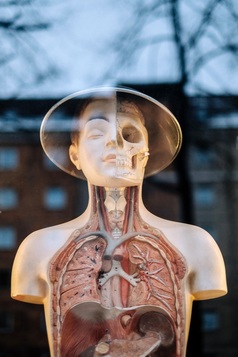

Educator Insights breakdown theory and research to give teacher practical advice and strategies. In his book, The Body Keeps Score, Dr. Van Der Kolk, one of the leading researchers in the area of psychological trauma, uses recent scientific advances to show how trauma literally reshapes both body and brain. Click on the picture below to check the book out on Amazon.com. Keep reading for a summary of chapter 4 of the book.

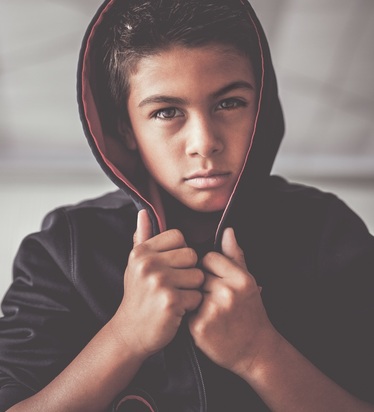

Chapter #4 of 20: The Anatomy of Survival To understand post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), we must first understand the human stress response. In this chapter, Dr. Van Der Kolk uses vivid metaphors to explain how the stress response changes in those with PTSD. Organised to survive: How the brain keep us safe The chapter starts with a description of the pervasive impact of trauma on our lives. “Trauma affects the entire human organism - body, mind, and brain. In PTSD, the body continues to defend against a threat that belongs to the past. Healing from PTSD means being able to terminate this continued stress mobilisation and restore the entire organism to safety” Dr. Van Der Kolk describes here what others refer to as toxic stress - the persistent and ongoing stress response to real or imagined threat. It’s important to note here that not everyone exposed to a frightening event necessarily develops trauma. Dr. Van Der Kolk reminds us that it is the perception of the inability to take ’effect action’ - to fight or flee - to protect ourselves that leads people to develop PTSD. It is easy to imagine how children exposed to repeated abuse and neglect can develop this ’immobilisation’ or ’learned helplessness’ in the face of ongoing threat. Click here to watch a video about ’toxic stress’ from TED-ED. Education Insight: I find it useful to remember that several traumatised children don’t enjoy school and feel forced to attend. I try to stay empathic to this by trying to remember how stressful it is for me when I’m forced to do something I don’t want to. These children are aware that any attempts to avoid school (through truancy or absconding) will be punished. They are also aware any mistakes made (as part of trying to participate in work) might come with aversive consequences as well - be it from teachers who think they are not trying hard enough, or other students who “think they are stupid”. Inhabiting this perception of these traumatised students reveals how school can prompt a sense of ’learned helplessness’. You are at the mercy of a system that doesn’t accommodate you, and tries to change your behaviour through punishment. We’re all programmed to get control over stress - to gain a sense of mastery and self-efficacy. When traumatised students see no opportunities to excel, have their efforts acknowledged or to be the best at something in school, they strive to become the best at being bad. Such behaviour might get them into more trouble, but it gives them a sense of mastery, control and predictability in their lives. It gives them the tools to dull the toxic stress response in their bodies, and gives their lives purpose and meaning. Like a infection in a wound, the longer we leave it, the harder it becomes to treat. The brain from bottom to top: The emotional brain and rational brain. A key concept in understanding trauma is ’state-dependent functioning’. In times of heightened stress - when we are in a ’state’ of heightened distress - we lose access to parts of our brain that guide reasoning and rationality - our functional capacity to make informed decisions. To explain this concept, Dr. Van Der Kolk introduces the ’triune brain’ - the key parts of our brain involved in our stress response. “The brain develops from bottom up. The reptilian brain develops in the womb and organises basic life sustaining functions. It is highly responsive to threat throughout our entire life span” The reptilian brain, known more commonly as the ’brain stem’ is described as being in-charge of “basic housekeeping” - arousal, sleep/wake, hunger/satiation, breathing and chemical balance. The limbic system, described as the ’seat of human emotion’, functions to map the relationships between ourselves and our surroundings, coordinate our emotional responses, categorise our experiences and control our perception and meaning-making of the world around us. “The limbic system is organised mainly during the first six years of life but continues to evolve in a use-dependent manner. Trauma can have a major impact of its functioning throughout life” “The prefrontal cortex develops last, and also is affected by trauma exposure, including being unable to filter out irrelevant information. Throughout life it is vulnerable to go offline in response to threat” The prefrontal cortex leads planning and anticipation; providing us with a sense of time and context, inhibition of inappropriate actions and empathic understanding. Education Insight: Learning about the ’triune brain’ changed the way I looked at behaviour management. Each of the three areas linked to three different aspects of classroom management for teachers. The ’reptilian brain’ is best controlled through ’autoregulation’ - things that we do as part of our daily routines that help us stay level, energised and not overly aroused. A cup of coffee in the morning, the lunch break, the early morning run. So how can we structure our daily classroom routines and rituals to keep kids regulated through the day? How can we differentiate these practices, to accommodate everyone’s needs? The easiest way to do this is through ’brain breaks’ - periodic breaks in the day to encourage movement and support cognitive functioning. If you haven’t already, click here to watch a video about GoNoodle - a free brain break resource. The limbic area, the seat of our emotions, corresponds to strategies relating to ’coregulation’ - how we conduct ourselves in our relationship with students to support them with their stress and emotions. Proactive strategies to build trust and understanding, combined with reactive communication strategies in the classroom, help traumatised student feel valued and not threatened to make mistakes and learn. Mostly, the students feel cared for, and know that when they are upset or agitated they can approach the teacher for help and support. Finally, the prefrontal cortex, relates to ’self-regulation’. The social-emotional skills we take for granted with other children, often require teaching for traumatised children. This can, however, only happen when the student is calm-enough, trusts the teacher enough, and is engaged enough in the material to see its relevance and utility in their lives. This can seem like a difficult task, but with coaching and supported reflective practice, teachers can understand the fundamental axiom of effective classroom management: children who are excessively stressed, do not learn. Click here to check out this great quick video from Neuropsychotherapy explaining the triune brain. Identifying danger: The cook and the smoke detector So how does the emotional and rational parts of the brain interact when faced with threat? Dr. Van Der Kolk uses the analogy of the cook and the smoke detector to describe the two neural response pathways that are the precursors to the fight-flight-freeze response. “The emotional brain has first dibs on interpreting incoming information. Sensory information about the environment and the body state received by the eyes, ears, touch, kinesthetic sense etc...converge on the thalamus, where it is processed and then passed on to the amygdala to interpret its emotional significance. This occurs with lightening speed. If a threat is detected the amygdala sends messages to the hypothalamus to secrete stress hormones to defend against the threat” “It’s important to have an efficient smoke detector: You don’t want to get caught unawares by a raging fire. But if you go into a frenzy every time you smell smoke, it becomes intensely disruptive. Yes, you need to detect whether somebody is getting upset with you, but if your amygdala goes into overdrive, you may become chronically scared that people hate you, or you may feel like they are out to get you” “The second neural pathway, the high road, runs from the thalamus, via the hippocampus and anterior cingulate, to the prefrontal cortex, the rational brain, for a conscious and much more refined interpretation. This takes several microseconds longer. If the interpretation of threat by the amygdala is too intense, and/or filtering system from the higher areas of the brain are too weak, as often happens in PTSD, people lose control over automatic emergency response, like prolonged startle or aggressive outbursts” Check out this video from Dr. Dan Siegal where he speaks about the ’low road’ and ’high road’ responses to stress, its links to triggers and dysregulation of emotions and behaviour. Educator Insights: Using the cook and smoke alarm analogy, I explain how sometimes, when the cook is feeling particularly insecure, they may make excuses for why their kitchen’s smoke alarm went off when it shouldn’t have. For traumatised students, lying about their misbehaviour (that may have been prompted by the quick, emotional pathway) can be thought of their way of re-establishing some sense of control and order in their world. The acceptance of responsibility, in this context, is admitting to others, and more importantly, themselves, that they are at the mercy of their faulty ’smoke alarm’. For some students, this is a truth they would rather not acknowledge. For others, this knowledge, flows into the already large pool of shame they feel about themselves. Without a sufficient acknowledgement of the impact of their past and trauma, such students move on with their lives feeling like they are damaged, bad and beyond the scope of being helped. This might sound strange to some reading, but I feel a sense of relief when I see a traumatised students fighting the facts and standing up for themselves. It makes me realise they haven’t resigned to feeling helplessness. So what’s the way forward? The message to be sent to these students through our words and actions is this: All is not lost, we can get through this together. The smoke alarm can be fixed - it’s just going to take some time and effort. Controlling the stress response: Top-down and Bottom-up “When our emotional and rational brains are in conflict……a tug of war ensues. This war is largely played our in the theater of visceral experience - your gut, your heart, your lungs - and will lead to both physical discomfort and psychological misery” What can be done to regulate this toxic stress response? Dr. Van Der Kolk describes the top-down and bottom-up approaches to stress regulation. “Structures in the emotional brain decide what we perceive as dangerous or safe. There are two ways of changing the threat detection system: from top down, via modulating messages….or from the bottom up, via the reptilian brain, through breathing, movement and touch” Traditional approaches to treating trauma has relied primarily on top-down approaches - talk therapy that involves the engagement of cognitive capacities or the rational brain. Although such approaches are effective, in times when the emotional brain overtakes these capacities, a bottom-up approach is required. Such somatic approaches, reinstate a sense of safety and help children feel calm enough to then engage in the traditional top-down approaches. Click here to watch Peter Levine explain the role of sensory and somatic symptoms in recovering from trauma. Educator Insights: So much of our education is top-down. We take this for granted - that children learn by listening to us talk at them. We carry this logic to teaching and supporting behaviour as well. As teachers, we are constantly inundated with information about using a ’participatory teaching methods’ and to move away from ’passive’ learning strategies. We’re reminded about the Confucius quote: “I see and I forget. I hear and I remember. I do and I learn”. What if we took this ’participatory framework’ to design scaffolded learning experiences that provide all students opportunities to act prosocially, while also learning the curriculum. By acting first (bottom-up) and then offering space and time for reflection later (top-down), we can be more inclusive, teach social-emotional skills, and make our curriculum engaging for our students. This challenge lies at the heart of effective differentiated classroom management. Having supported several teachers in generating differentiated learning plans, I am often struck by how much the teachers enjoy this process. It is like they have been given permission to be creative, take risks and be thoughtful about the needs of their class. I had a teacher say to me “this is the reason I became a teacher. To be innovative and creative, while still making a difference in the lives of my students” When did our systems stop giving teachers permission to function this way? Why haven’t we invested in coaching and mentoring that supports teachers to engage in reflective practice to function to their full potential? I once heard one of my behaviour support colleagues say to a classroom teacher ’remember the acronym: Q-T.I.P. It stands for “quit taking it personally’’ Although there was some wisdom to this advice, I wondered about what it must be like for this teacher. We expect them to manage incredibly difficult children, by delivering an overloaded, standardised curriculum, with restrictions about how they can deliver it to their student, with little or no other support. Much like the traumatised students, I see teachers feeling helpless when faced with challenging students. Their reactions of frustration and anxiety are all legitimate, in the reality of their work environment. We have all been down the ’low road’ - tough days where everything feels personal. I have spent several years helping teachers take the ’high road’ - one where they can make sense of a student’s behaviour, think about learning needs and continue to stay empathic. Just as traumatised students risk their reputation and safety by attending school, we as teachers, must also embrace the risks that come with getting things wrong when acting inclusively. To listen to our ’smoke detectors’ but not let it make us risk-averse and feel constrained by a narrow interpretation of what can and cannot be done. I have found that it starts with one successful attempt at being inventive for systems to pivot and become receptive to doing things differently. Educational systems, much like students and teachers, require hope and inspiration to serve all members of its community well. To learn about the Trauma Informed Positive Behaviour Support (TIPBS), visit www.tipbs.com and register your interest in our online course. The first 100 sign-ups can do the course for free. Click here to register your details.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

February 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed